STRENGTH & CONDITIONING

Building a strong, capable, resilient body that serves your artistry.

Creating your own training regimen is the next step. You just need the right framework, built specifically for the demands of dance. Here, you’ll learn how to structure your own workouts, pick the right types of exercises, and guide your training to meet your goals.

TRAINING DOMAINS

Learn how cross-training with a focus on key physical capacities translate directly to performance on stage.

(Ngo et. al, 2024; Koutedakis et. al, 2005; Long et. al, 2021)

-

Strength is the foundation for movement control. In dance, this doesn’t mean lifting the heaviest weights. It means training your muscles to stabilize, support, and move with precision under pressure. Strength training develops the force production necessary to lift your own body efficiently, hold challenging positions, and control and initiate movement from a stable base.

-

Power and speed training are critical for dynamic performance. Power is your ability to generate force quickly: think explosive jumps, fast direction changes, or dynamic accents. Speed training improves your reaction time and muscular firing rate, which helps in quick transitions and timing-sensitive movement. Plyometric exercises (like jump squats or bounding drills) and resisted sprints or agility ladders help dancers improve textures, perform quicker pick-ups in footwork, and have greater ease in jumps that once felt difficult.

-

Endurance training improves your heart and lungs’ ability to supply oxygen to working muscles, allowing you to perform longer without fatigue. In dance, this translates into stamina—not just to survive a piece, but to sustain high performance quality throughout. Whether you’re running a 90-minute tech rehearsal or performing a six-minute high-intensity routine, cardiovascular endurance ensures that your technique doesn’t falter from exhaustion.

Dancers who incorporate aerobic cross-training like swimming, cycling, or high-rep bodyweight circuits often report feeling more energized during class and able to execute choreography fully, even at the end of a demanding rehearsal.

-

As a dancer, flexibility is embedded in your technique. But there’s more to flexibility than just reaching extreme ranges. To move with both freedom and control, dancers need mobility: the ability to move actively and efficiently through a joint’s full range of motion.

While traditional stretching might help muscles feel looser, true mobility training focuses on strengthening your joints and muscles at their end ranges. This creates usable, dance-ready range that directly translates into better lines, cleaner transitions, and reduced injury risk.

-

While performance is the visible side of dance, injury prevention is what makes a long-term dance career possible. Joint protection involves creating strength and mobility around your most vulnerable areas, like the hips, knees, ankles, shoulders, and spine. Stability training ensures that muscles and joints work together efficiently to absorb force and reduce strain. This is especially critical in high-impact movements and repetitive choreography.

Exercises that train hip alignment, foot strength, shoulder stability, and core coordination are essential for reducing overuse injuries, sprains, and chronic pain. Dancers who prioritize joint stability often report fewer flare-ups during performance season and faster recovery after long rehearsal days.

Whether you want to get better at holding levels, improve textures, or perfect your timing, understanding your goals as a dancer will help you prioritize these target areas in your workouts to ensure you’re training with intention.

The Building Blocks of Your Training Routine:

How do I structure my workouts?

Before we dive in, know this: every dancer is different, and so is every training plan. The best workout structure is the one that supports your unique body, goals, schedule, and performance demands.

That said, most effective training sessions follow a general structure that supports optimal performance, injury prevention, and progressive improvement. The sequence below is a suggested format for dancers who want to build strength, speed, and resilience all while respecting the physical demands of dance.

Let’s break it down:

(National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2015)

1. WARM-UP.

Get your joints moving, your muscles activated, and your nervous system primed for action.

2. POWER/SPEED/AGILITY.

Your body is ready for short, explosive movements to generate force quickly at high intensities.

3. RESISTANCE/STRENGTH.

Focus on major movement patterns to build control & initiate from a stable base.

4. CARDIO/CORE/ACCESSORY.

These “finishers” improve your stamina, target the small stabilizing muscles and correct imbalances.

TRAINING VARIABLES

How do I prevent overtraining?

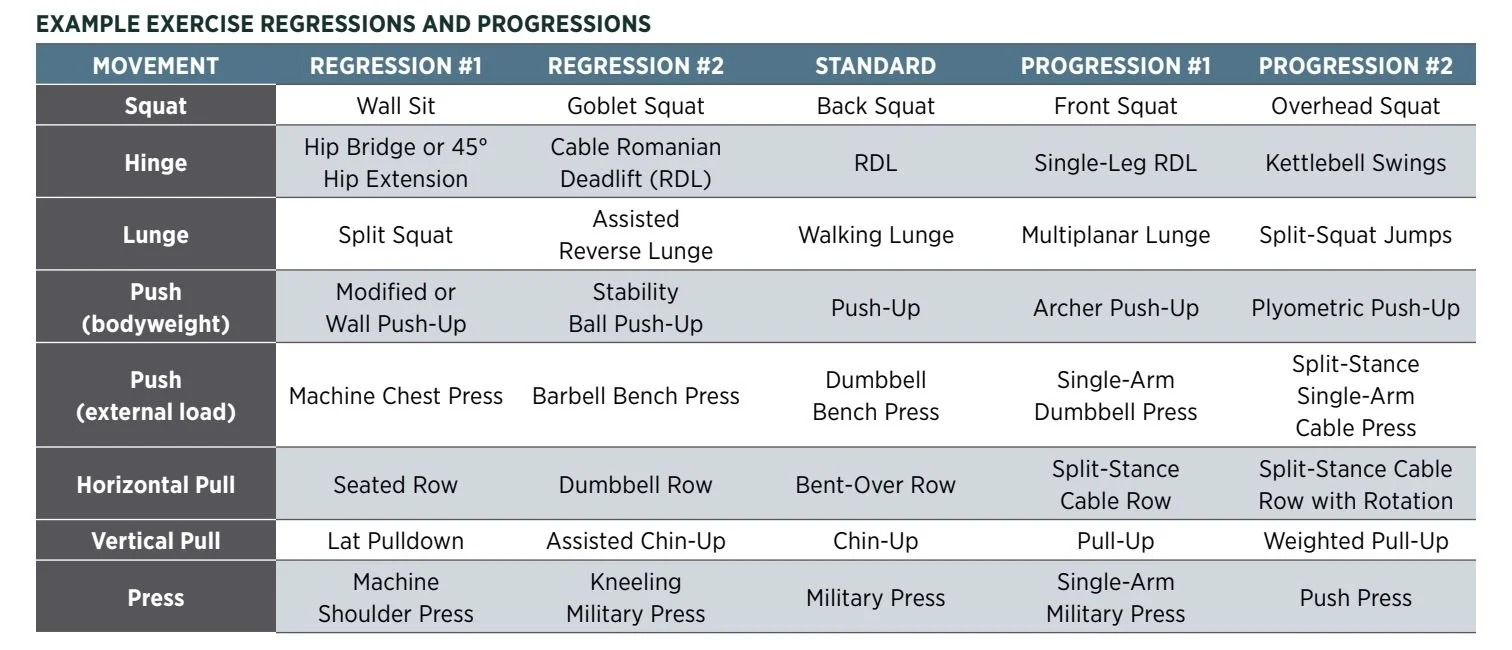

Performing an exercise that’s too advanced for your current strength, mobility, or technique can lead to compensation, poor form, and ultimately injury. Regressions and progressions allow you to modify variables (load, range of motion, body position, etc.) in your workout to make them less or more challenging:

+

PROGRESSIONS

Make an exercise more challenging and allows you to level up once your body is ready, so you're always adapting and growing without plateauing.

-

REGRESSIONS

Modifications that scale an exercise down, making it safer or more manageable to ensure you're training with control, quality, and safety when you're fatigued or returning after time off.

(Cai et. al, 2024)

Training should meet you where you are—then move you forward. That’s how you build strength and longevity.

How hard should I push myself?

The key to sustainable progress, especially for dancers, is that it’s not just about how much you lift. It’s about how it feels. Everyone has different energy levels from day to day depending on sleep, stress, nutrition, and recovery. That’s where RPE, or Rate of Perceived Exertion, comes in.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

RPE is a tool used in strength training to help you monitor how hard an exercise feels on a scale from 1 to 10. It accounts for how you feel in the moment and adjusts for real-time feedback your body is giving you. In other words:

your body is the coach.

Why should I use RPE?

Considers everyday preparedness

Enhances mind-body awareness

Optimizes recovery & prevents injury

Tracks progress

(Morishta et. al, 2018)

10

MAX EFFORT ACTIVITY

Feels almost impossible to keep going. Completely out of breath, unable to talk. Cannot maintain for more than a very short time.

9

VERY HARD ACTIVITY

Very difficult to maintain exercise intensity. Can barely breathe and speak only a few words.

7-8

VIGOROUS ACTIVITY

Borderline uncomfortable. Short of breath, can speak a sentence.

4-6

MODERATE ACTIVITY

Breathing heavily, can hold a short conversation. Still somewhat comfortable, but becoming noticeably more challenging

2-3

LIGHT ACTIVITY

Feels like you can maintain for hours. Easy to breathe and carry a conversation.

1

VERY LIGHT ACTIVITY

Hardly any exertion, but more than sleeping, watching TV, etc.

REFERENCES

Cai, A., Song, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, J., Wang, M., & Tang, L. (2024). Effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 87, 101967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.101967

Koutedakis, Y., Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou, A., & Metsios, G. (2005). The significance of muscular strength in dance. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 9(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089313X0500900106

Morishita, S., Tsubaki, A., Takabayashi, T., & Fu, J. B. (2018). Relationship between the rating of perceived exertion scale and the load intensity of resistance training. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 40(2), 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000373

National Strength and Conditioning Association. (2015). Foundations of fitness programming [PDF]. Author. https://www.nsca.com/contentassets/8323553f698a466a98220b21d9eb9a65/foundationsoffitnessprogramming_201508.pdf

Ngo, J. K., Lu, J., Cloak, R., Wong, D. P., Devonport, T., & Wyon, M. A. (2024). Strength and conditioning in dance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 24(6), 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsc.12111